COVID-19 Disease Report for King County, Washington

Structural Causes of Disease Report for COVID-19 in King County, WA

- 🖊️ Author: Leah Caragol

- 📆 Publish Date: November 24, 2022

- 🗒️ Type: Academic Disease Report

- 🏫 Association: Kings College London

Covid-19 - King County Facility A Report

Published 2 July 2020

This paper aims to follow the format of the WHO disease report because it provides an effective composition for this report.

Outbreak at a Glance

On 31 December 2019, cases of an unfamiliar respiratory virus were first reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China (Newsholme, 2022). The virus was determined to be coronavrisu. Since the initial detection, more than 10.8 million cases of Covid-19 and more than 128,000 deaths have been confirmed globally (JHU, 2020). On 20 January 2020, the first case was reported in the United States in Snohomish/King County, Washington. On 28 February, Public Health-Seattle and King County (PHSKC) was informed of a positive case of an individual who resided in a long-term care facility (LTCF) in Kirkland, Washington (McMichael et al., 2020). As of 18 March, 167 confirmed cases were epidemiologically linked to the facility (McMichael et al., 2020). Patients with the illness frequently present symptoms of cough, fever, and shortness of breath (CDC, 2020). WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020 (McMichael et al., 2020).

In the context of rapidly escalating Covid-19 outbreaks, this report will introduce Covid-19 and focus on the long-term care facility where the first outbreak in the United States was recognized to discuss public health responses, lessons learned, and potential interventions.

Epidemiology of COVID-19

Covid-19 is an infectious respiratory illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 (CDC, 2020). Most early cases of Covid-19 were epidemiologically linked to Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, from Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which sells live animals, among other goods (Zhai et al., 2020). This suggests that coronavirus spilled over from animals to humans. People with Covid-19 may have a wide range of symptoms – most likely appearing 2-14 days after initial infection due to exposure to the virus (CDC, 2020). Due to the broad incubation period, high transmission rates are likely to occur. Symptoms generally include fever or chills, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, body aches, headache, loss of taste or smell, sore throat, nausea and vomiting, and diarrhea (CDC, 2020). Individuals can be presymptomatic, symptomatic, or asymptomatic and still transmit the virus. Covid-19 affects all populations; however, individuals with pre-existing conditions like diabetes, chronic kidney disease, asthma, cardiac disease, or respiratory issues may experience worse illnesses (CDC, 2020).

Using the SARS-CoV-2 CDC protocol, testing is performed by rRt-PCR from a cotton swab administered via the nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal routes (Zhai et al., 2020). This is the only testing option; it can take up to 24-48 hours to receive test results.

Outbreak Overview

On 20 January 2020, the first patient in the United States was confirmed to have Covid-19 in Washington. The patient, a 35-year-old male, presented with a persistent dry cough, nausea, and vomiting to an urgent care facility on 19 January (Holshue et al., 2020). Before seeking care, the patient had had a cough and fever for four days. He had reported returning from travel to Wuhan, China, where positive cases of Covid-19 were rising. An earlier health alert from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) which discussed the novel coronavirus cases in China prompted him to see a provider (Holshue et al., 2020). The patient was admitted and tested for all respiratory viruses. Following a confirmed positive test for Covid-19, with the coordination of the Washington Department of Health, CDC, and local health officials, he was moved to an isolation unit in Seattle (Holshue et al., 2020). He was further monitored and evaluated for 12 days until he tested negative. Contact tracing ensued, and 70 contacts were identified and monitored for the onset of symptoms, though there were no other cases (Newsholme, 2022).

Shortly after, on 28 February, PHSKC was notified of a positive case from an admitted 73-year-old female, tested using CDC testing criteria (McMichael et al., 2020). The patient lived in a long-term care facility (LTCF), Life Care Centre (Facility A), in Kirkland, Washington. She had no previous travel or was known to have contact with Covid-19. Prior, two residents from the same facility died on 26 February from an unidentified respiratory illness and retrospectively tested positive for Covid-19. The 73-year-old resident was admitted to EverGreen Hospital Kirkland with tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxemia (McMichael et al., 2020). Her medical history included “type II diabetes, obesity, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure” (McMichael et al., 2020). A positive rRT-PCR was displayed on February 28, 4 days after hospital admission. The patient died on 2 March 2020 (McMichael et al., 2020). On 1 March, one staff member tested positive after working with symptoms on 26 February (McMichael et al., 2020). On 5 March, the facility was informed that another confirmed positive resident had been hospitalized (McMichael et al., 2020). The facility then began immediately restricting visitors, and communal activities were canceled.

Public Health Response

In response to the positive result on 28 February, PHSKC and a CDC field team immediately began an investigation at Facility A. Interviews by phone were carried out for residents, visitors, and healthcare personnel with confirmed Covid (McMichael et al., 2020). They were asked to provide information on symptoms, travel, pre-existing conditions, and close contacts to confirmed covid cases. This team guided individuals to self-isolate and self-quarantine. Anyone in close contact with the interviewees who had symptoms could be tested (McMichael et al., 2020). By 6 March, PHSKC and CDC recommended all staff wear eye protection, a gown, gloves, and a face mask near symptomatic residents (McMichael et al., 2020). At this time, staff was also instructed to assess residents twice daily for symptoms and at the beginning of all worker’s shifts. On 10 March 2020, Washington Governor Jay Inslee implemented mandatory health screenings for healthcare workers and visitor restrictions for all licensed facilities (McMichael et al., 2020). Other prevention strategies suggested included measuring body temperature for fever, sending home symptomatic workers, monitoring residents closely, restricting staff movement, and training on PPE.

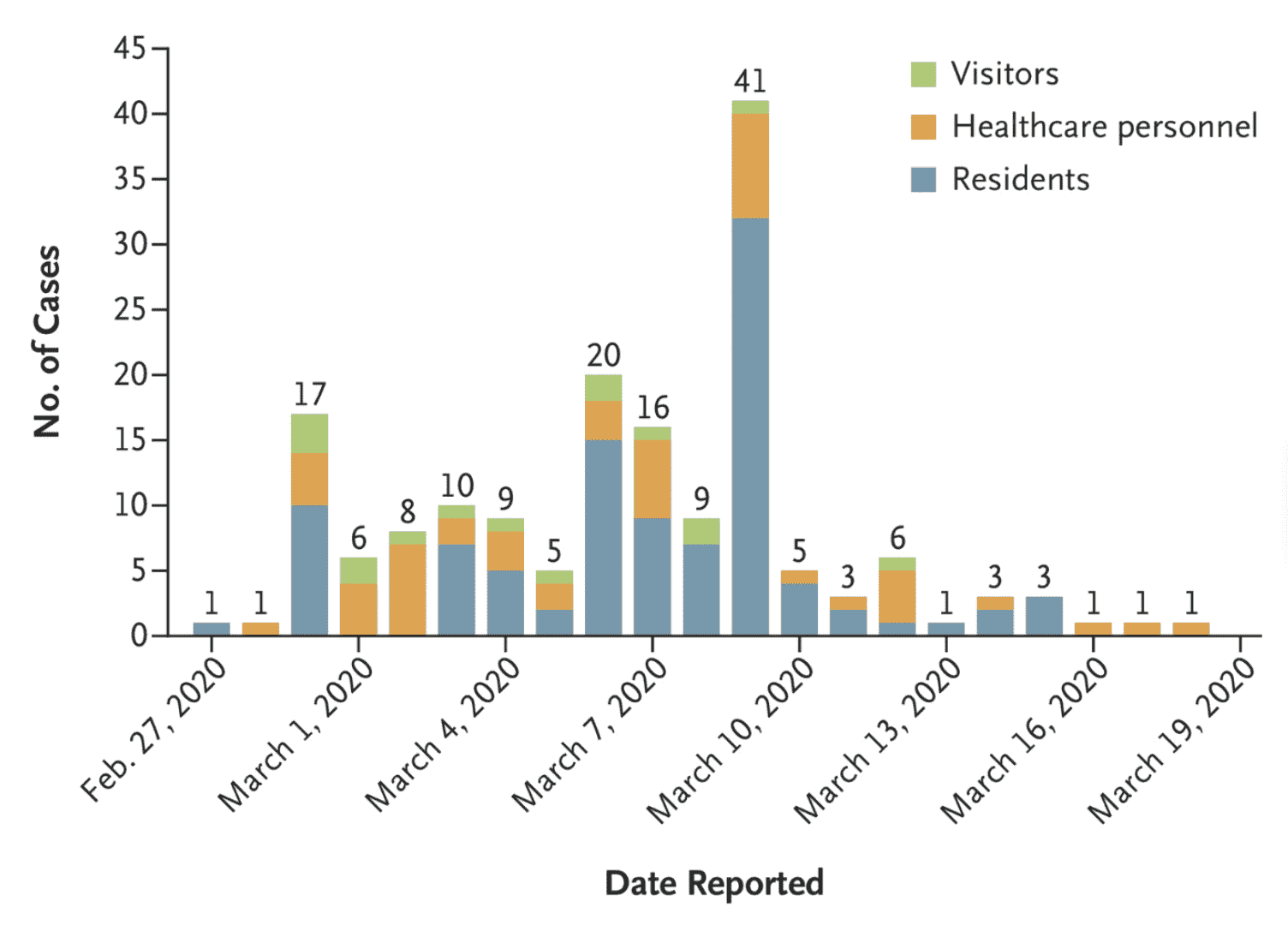

As a part of the response, PHSKC and CDC contacted at least 100 long-term care facilities in King County to identify clusters of influenza-like illness through a voluntary survey (McMichael et al., 2020). All care facilities with evidence of clusters were informed of infection control strategies at the time. Facilities with high cases of symptomatic residents were visited for diagnostic testing and to implement, train, and support infection control measures. By 18 March, 30 King County facilities, including Facility A, had at least one confirmed Covid-19 case (McMichael et al., 2020). Two of these facilities had epidemiological links to Facility A - from staff working at both places. Figure 1 shows cases connected epidemiologically to Facility A over this period.

Figure 1: Cases Epidemiologically Linked to Facility A (McMichael et al., 2020).

Methods

On 8 March 2020, the ongoing PHSKC and CDC investigation offered testing to all residents at Facility A. Swab collection and diagnostic testing were administered following the CDC guidelines. Patients were defined as asymptomatic for residents with a positive test, and no symptoms were present two weeks before or after the positive test was performed (Tobolowsky et al., 2021). Presymptomatic persons were defined as infected residents without symptoms at the time of testing but developed them within two weeks after. Symptoms monitored were in guidelines with the CDC. Outcomes assessed included positive cases and a number of deaths in the study population at Facility A.

Results

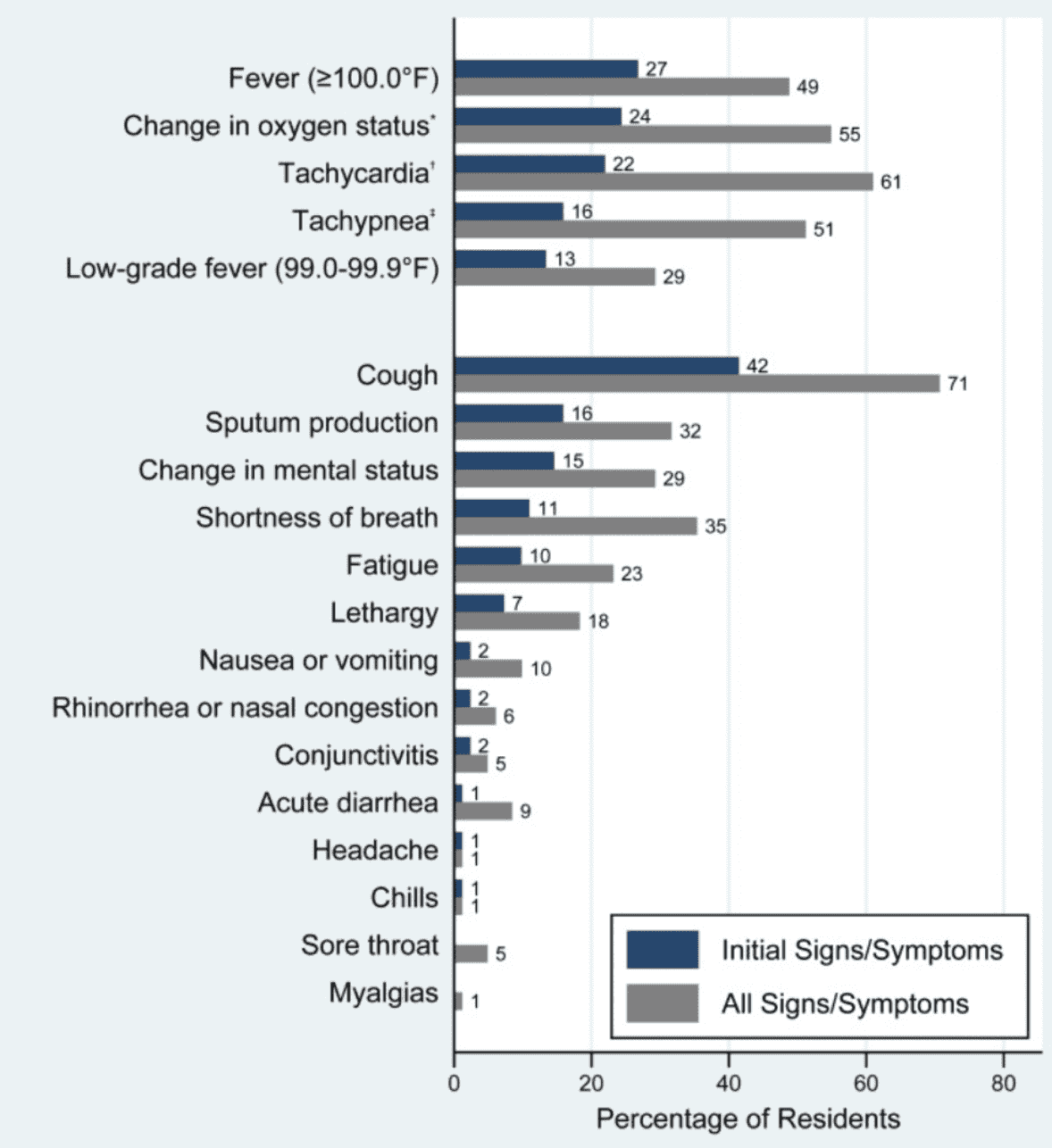

There were approximately 130 residents at the time at the beginning of the outbreak. From 28 February - 16 March, 118 individuals were tested for Covid-19 either out of suspicion from symptoms or facility-wide testing. Of the 118 tested, 101 were confirmed to be positive for Covid-19 (Tobolowsky et al., 2021). Thirty-five residents had died from the facility by 18 March. Four of those positives were asymptomatic, and 12 were presymptomatic (Tobolowsky et al., 2021). For the remaining positive cases, the most common symptoms were cough, fever, tachycardia, and change in oxygen status. 90.2% of residents presented with one or more of these symptoms at the start of the illness (Tobolowsky et al., 2021).

Figure 2: Signs and symptoms of Facility A residents with Covid-19 (Tobolowsky, et al., 2021).

Discussion

Covid-19 can spread rapidly once introduced into LTCFs, resulting in substantial mortality and morbidity. Therefore, routine screening of Covid-19 among residents and staff should include the five most common signs and symptoms from Figure 2. Since there is a likelihood for asymptomatic and presymptomatic people to play an important role in transmission in this vulnerable population, additional prevention measures should be considered, including facility-wide testing. Additionally, proactive steps should be taken, if not already, to restrict visitors, require face masks, and implement strict staff screening.

Recommendations

There are many learning opportunities for LTHCFs as a result of this pandemic. Facility A successfully implemented the PHSKC and CDC’s recommendations. However, there were some limitations, including a slow response time from the first confirmed facility case and control measures, the mobility of staff, and symptom-based testing. The facility began the usage of masks on 6 March, even though the CDC did not formally recommend the use until 24 March (Arons et al., 2020). Staff’s mobility made them remain potential sources of Covid-19 introduction. Additionally, testing was only symptom-based. By not testing and quarantining the entire facility, cases were able to spread between residents and other LTC facilities.

The report recommends the following for Facility A

1. Target Interventions at Staff

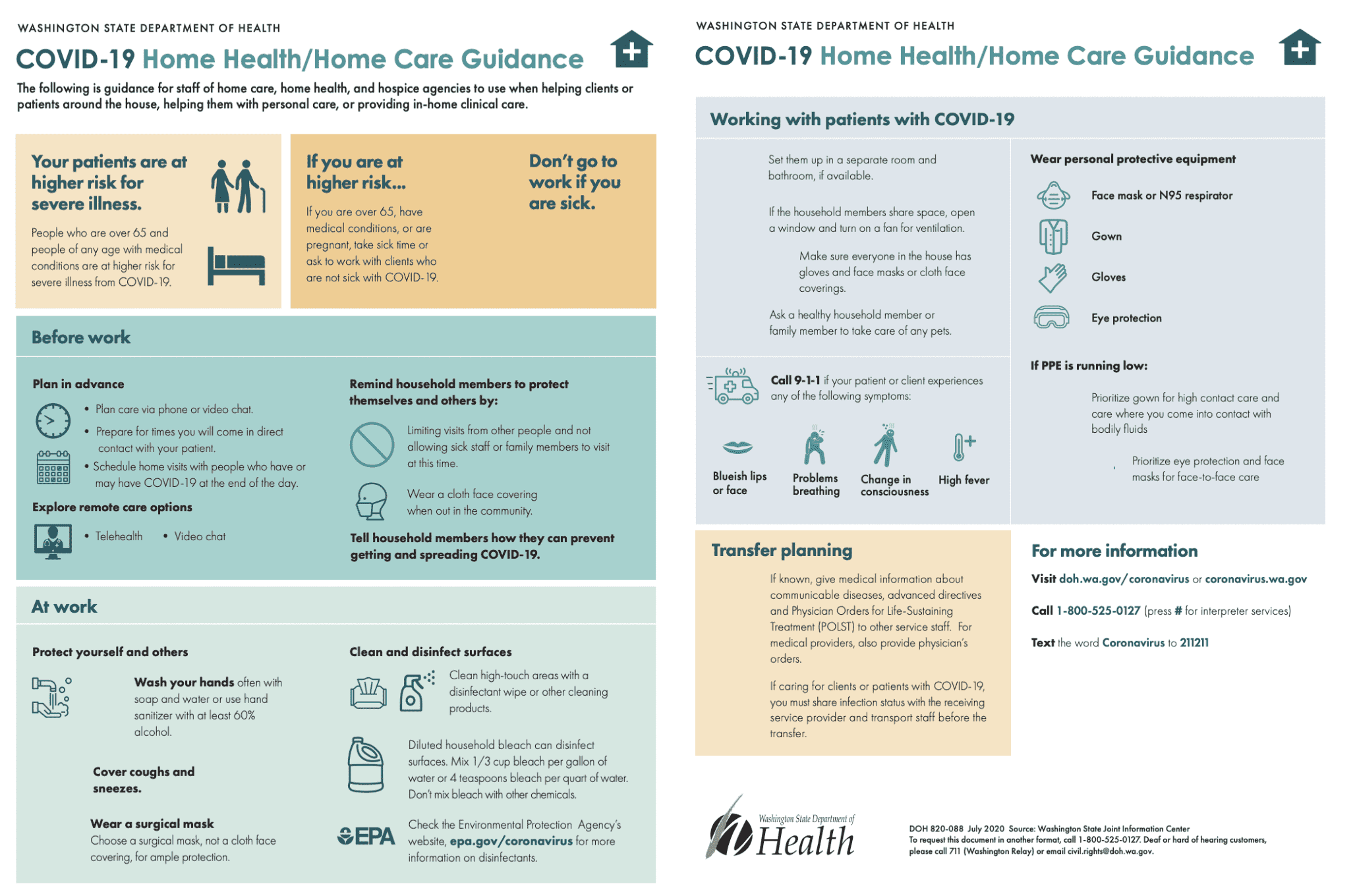

Staff is substantially more infectious than residents because they typically care across the entire facility and for multiple residents and interact with other staff (Adams et al., 2022). Residents were confined mainly to their rooms, so the staff was a transmission mode. Ensuring access to PPE and training, regular testing and screening, and consistent documentation of the staff member’s whereabouts can help limit transmission or contact trace and test. In addition, there should be a staff checklist at the entrance of each room, and staff should not be allowed to wear the same gloves or gown in residents’ rooms. Figure 3 shows guidance from the Washington Department of State Health for staff should be sent and posted around the facility.

Staff is substantially more infectious than residents because they typically care across the entire facility and for multiple residents and interact with other staff (Adams et al., 2022). Residents were confined mainly to their rooms, so the staff was a transmission mode. Ensuring access to PPE and training, regular testing and screening, and consistent documentation of the staff member’s whereabouts can help limit transmission or contact trace and test. In addition, there should be a staff checklist at the entrance of each room, and staff should not be allowed to wear the same gloves or gown in residents’ rooms. Figure 3 shows guidance from the Washington Department of State Health for staff should be sent and posted around the facility.

Figure 3: WADOH guidance for staff (WA DOH, 2020).

2. Test all Residents and Staff and Establish Zones for Positive Residents

Due to presymptomatic and asymptomatic residents and staff, symptom-based testing is not the most effective measure for reducing the spread of illness. Facility-wide testing should have occurred at the earliest notification of Covid-19. Staff could have then implemented control measures such as separating positive patients into a locked wing.

A successful case to consider containing an outbreak was in a geriatric psychiatry unit in King County, Washington. Between March 11-18, nine inpatients and seven staff members were confirmed to have Covid-19 infection (Constantino-Shor et al., 2020). All patients were immediately isolated, regardless of their symptom status, and subsequently tested. Positive patients were transferred to the locked East wing. They were serially retested until negative. Then they would be moved to the locked West wing (Constantino-Shor et al., 2020). A checklist was created for PPE donning and doffing for staff, and trained observers were essential in supporting safe PPE control measures (Constantino-Shor et al., 2020). Visitations were also prohibited during this time. On 2 April, the Covid-19 positive unit was turned into a “hot zone” where patients could share common spaces, dining, and activity rooms to socialize (Constantino-Shor et al., 2020). Staff-led interventions were also enforced and confirmed that staff was required to quarantine for ten days and be symptom-free for 72 hours before returning to work. This example provides essential insight into interventions Facility A could have potentially enforced. In this case report, testing all individuals immediately and isolating them limited the spread of Covid-19 from the beginning.

3. Improve Safe Measures of Social Interaction

All residents in Facility A were isolated from their rooms during the outbreak. Loved ones were no longer allowed to visit and all community activities had been canceled. Many residents reported feeling lonely and stressed since the beginning of the outbreak (Lai et al., 2020). These feelings can make it more likely for residents to refuse to isolate or make it challenging for staff to enforce. By increasing interventions to reduce loneliness, the necessary isolation could be easier. One suggestion is using technology to an advantage. Every resident should be able to video chat with their friends and family. Increasing technology could also allow telemedicine for daily check-ins to limit staff exposure (Lai et al., 2020). Giving adults in LTC facilities the ability to access technology could allow them to maintain/create social connections and communities.

Conclusion

Residents in LTCFs are a vulnerable population susceptible to high mortality. LTCFs should be well-prepared to manage Covid-19. Appropriate control measures, including restricting visitors, testing, frequent symptom checks, and proper PPE, should be established and followed to prevent transmission inside and outside the facility.

References

Adams, C. et al. (2022) “The role of staff in transmission of SARS-COV-2 in long-term care facilities,” Epidemiology, 33(5), pp. 669–677. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000001510.

Arons, M.M. et al. (2020) “Presymptomatic SARS-COV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility,” New England Journal of Medicine, 382(22), pp. 2081–2090. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2008457.

Constantino-Shor, C. et al. (2020) “Containment of a COVID-19 outbreak in an inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry Unit,” Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 27(1), pp. 77–82. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390320970653.

Covid-19 home health/home care guidance-en - washington (2020). Available at: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/ALTSA/covid-19/COVID-19HomeHealthAideGuidance-EN.pdf (Accessed: November 24, 2022).

Holshue, M.L. et al. (2020) “First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine, 382(10), pp. 929–936. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2001191.

JHU CSSE (2020) JHU CSSE COVID-19 Data, GitHub. Available at: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19 (Accessed: November 24, 2022). Lai, C.-C. et al. (2020) “Covid-19 in long-term care facilities: An upcoming threat that cannot be ignored,” Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 53(3), pp. 444–446. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.008.

McMichael, T.M. et al. (2020) “Epidemiology of covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington,” New England Journal of Medicine, 382(21), pp. 2005–2011. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2005412.

Newsholme, B. (2022) COVID-19, 1st wave, Seattle [PowerPoint Presentation]. King’s College London.

Symptoms of COVID-19 (2020) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html (Accessed: November 24, 2022).

Tobolowsky, F.A. et al. (2021) “Signs, symptoms, and comorbidities associated with onset and prognosis of COVID-19 in a nursing home,” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(3), pp. 498–503. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.01.070.

Zhai, P. et al. (2020) “The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19,” International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 55(5), p. 105955. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105955.